Amalia Mesa-Bains

Amalia Mesa-Bains is an internationally renowned artist, scholar, and curator. Throughout her career, Mesa-Bains has expanded understandings of Latina/o artists’ references to spiritual practices and vernacular traditions through her altar installations, articles and exhibitions. In 1992 she was awarded a Distinguished Fellowship from the MacArthur Foundation. Her work has been shown at institutions that include: the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art at Phillip Morris, and the New Museum, as well as international venues in Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Ireland, Sweden, England, France and Spain. In 2011, her work was featured as part of NeoHooDoo: Art for A Forgotten Faith, and in 2013, she recontextualized objects from the collections of the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles in New World Wunderkammer. As a cultural critic she has co-authored along with bell hooks, Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism. Mesa-Bains founded and directed the Visual and Public Art department at California State University at Monterey Bay where she is now Professor Emerita. Mesa-Bains community work includes board of trustee positions with the Mexican Museum in San Francisco and advisory boards for the Galeria de la Raza, and the Social Public Resource Center in Los Angeles.

New World Wunderkammer

©Photo courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA; Installation photography by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

An Interview with Amalia Mesa-Bains

MKM: Tell us about your childhood, where did you grow up? Were you always creative?

AMB: I grew up in Sunnyvale California in 1943 when it was rural and an agricultural center with orchards and canneries. Yes, I was creative and the third generation of artists in my family.

MKM: You began your education with a degree in art and ultimately earned a PhD in psychology. Can you tell us about this multi-disciplinary journey and how it informs your work?

AMB: I began with an art degree in painting, but eventually turned to new media and materials that include spray painted constructions. When I began my master’s degree, I was part of Teacher Corps, a program that recruited minorities to serve in minority communities. Because of Teacher Corps at San Francisco State University, I was lucky to be on a team assigned to schools in the Mission district with fellow Latino team members and a veteran educator Yolanda Garfias Woo, who became my mentor. She was good friends with many of the Chicano and Latin leaders in the Mission. Through her I was drawn into the Chicano Movement and dedicated my art to the cultural work of the movement. While teaching I began to realize the emotional and psychological needs of my students, so I began taking night classes in psychology. At the same time, I was in an artist’s dream group guided by my mentor and friend Renaldo Maduro, which led to my interest in clinical psychology. Eventually I went to the Wright Institute which moved me toward a multidisciplinary approach to art, culture and women’s development. This disposition has informed much of my work as an educator, artist and activist.

MKM: You are an artist, curator, educator, author and activist – how do each of these practices inform, inspire and support the other in your varied projects and your work in general?

AMB: I think my curiosity has driven much of the interconnected fields that I work in. Many of the themes and directions in my work are also present in my curating, writing and activism. In particular my commitment to making visible the work of Chicana and Latina artists.

MKM: When you’re creating what’s your daily routine? Rituals, patterns?

AMB: I generally gestate on projects for quite a while which involves a great deal of reading, research, and even interviews to put together the guiding concepts. This will lead me to image collecting – all of which eventually helps me frame the final project. I always keep a drawing project book as I go along where I paste in images, notes and drawings as the project unfolds. I don’t work in the morning, mainly the afternoon, and particularly afternoon and often middle of the night note taking. I have no rituals other than being sure the studio is ready with tools and art supplies in order and tables cleared.

MKM: Has your practice changed over time?

AMB: Only in so far as age and illness have required more planning for other fabricators and scheduling of supplies etc.

MKM: What is your most important tool when you are making art? Is there something you can’t live without in your studio?

AMB: Only my imagination, since I depend more on fabricators such as glass blowers, box builders etc.

MKM: Is there an artwork/installation you are most proud of? Why?

AMB: My favorite piece as an experience and process has been the “New World Wunderkammer” which allowed me to work with all the departments at the Fowler UCLA Museum, including their extraordinary collections. It was a two-year project with multiple visits and direct work with specialists, designers, education folks and others.

MKM: What has been a seminal experience?

AMB: In my early years as an artist, I was mentored by Yolanda Garfias Woo who introduced me to the Meso American world, as well as the traditions of Mexican folk forms including the Days of the Dead. My long mentorship and friendship with her has been life changing.

MKM: What memorable responses have you had to your work?

AMB: I have had many reviews and recognitions. The recent review in the New York Times for the opening of the new Kinder building at Museum of Fine Arts Houston was especially positive, but my very first review in “Art in America” in 1987 when my show “Grotto of the Virgins” at INTAR in New York was acclaimed as one of the 10 best shows in alternative galleries that year, it was inspiring.

MKM: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

AMB: Hang on and stay with your purpose.

MKM: You often work with objects and collections – Do you maintain any of your own collections or live with other artists’ work?

AMB: Yes, we have an extensive collection of Chicano, Latino and Black art.

MKM: What is your dream project?

AMB: I have always imagined a residency in a museum where I could rearrange my objects into different installations each week.

MKM: What are you working on right now?

AMB: I am currently working on a project for the Mac Arthur Fellows 40th Anniversary which is called “Dos Mundos: Mexican Chicago.” It will be at two sites and tell the story of the invisible history of Mexicans in the building of Chicago as well as an homage to my own family who were very active in the Mexican communities of Chicago.

MKM: Is there any subject or theme you’ve been particularly interested in lately?

AMB: I am always interested in the issues of the immigrant experience and also in the change in the natural world.

MKM: What do you have planned for the year ahead?

AMB: Completing the Chicago project, writing and readying myself for a potential retrospective in 2023.

New World Wunderkammer

New World Wunderkammer – Installation Photographs

©Photo courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA; Installation photography by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

One of Amalia Mesa-Bains’ favorite projects, for both the experience and process, was New World Wunderkammer. She was invited to create this installation at UCLA’s Fowler Museum in honor of the Fowler’s 50th anniversary, fall 2013 to spring 2014. New World Wunderkammer featured more than 75 rare and historic objects from the museum’s permanent collection. The objects were combined and recontextualized with many of Amalia Mesa-Bains personal items from previous installations.

Mesa-Bains is well known for her groundbreaking work creating altar installations reminiscent of the ofrenda, a traditional home altar intended to honor and memorialize the departed. Along with the spirit of the domestic ofrenda, Mesa-Bains incorporated an age-old institutional method of display for New World Wunderkammer: the “cabinet of curiosities” or “cabinet of wonder”. The cabinet of curiosity has its origins in Renaissance Europe as a mode for storing and displaying collected items intended to illustrate an owner’s knowledge of the world.

The Fowler Museum provided Mesa-Bains access to all of its collections and the freedom to compose New World Wunderkammer as she envisioned. Over the course of two years, she became familiar with thousands of precious objects and ultimately assembled three connected cabinets of curiosity, representing “Africa, the indigenous Americas and the complex cultural and racial mixture (Colonial mestizaje) that typifies the New World.” 1 In this setting Mesa-Bains invited viewers to explore the “collision” of these colonized cultures while offering new paths of understanding and healing for the objects, the people encountering them and the museum in which they reside. 2

New World Wunderkammer – Cabinet details

©Photo courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA; Installation photography by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

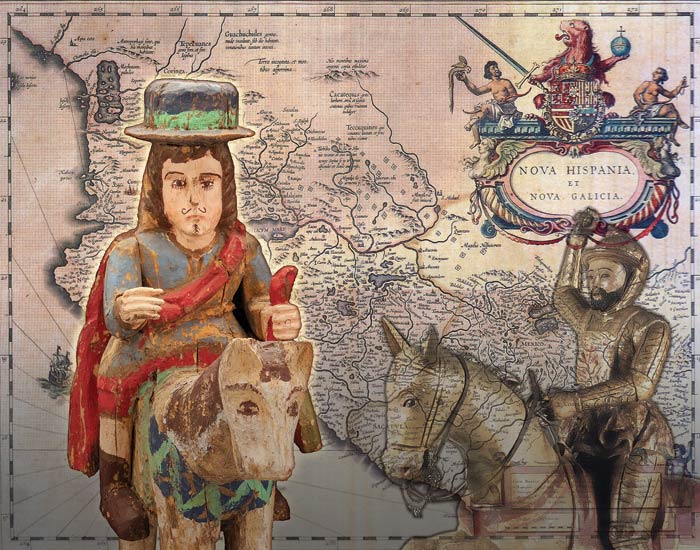

In addition to composing the cabinets, Mesa-Bains created eight giclée prints featuring images of specific objects in the exhibit. The object image is situated within compositions that include photographs, maps and plants that illustrate the context and history of the object’s origin. The prints were installed in proximity to the actual objects in the gallery cabinets. Study tables provided an interactive component within the gallery space, inviting visitors to participate in examining objects and history together.

New World Wunderkammer

The Map of Loss. Giclée print. 32 1/4″ x 26.” 2013.

It is easy to understand why New World Wunderkammer is Amalia Mesa-Bains’ favorite exhibit for the experience and process. Through her vision and inspirational creative process, Mesa-Bains produced a profound, multi-layered, inclusive and interconnected exhibition. New World Wunderkammer, brought together communities and cultures to create connection, honor memory and history, cultivate understanding and promote healing.

1. “New World Wunderkammer: A Project by Amalia Mesa-Bains” https://www.fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/fowler-at-fifty-new-world-wunderkammer/accessed 4/11/21

2. Lucian Gomoll, “The Performative Spirit of Amalia Mesa-Bains’ New World Wunderkammer.” Cultural Dynamics 27, no. 3 (November 2015): 359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374015610130

3. Ibid., 374.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid., 362.

6. Ibid., 364-66.